Nigeria and the CPI: Perception Versus Reality

February 26, 2018 | By Umar Yakubu

There is growing concern among anti-corruption agencies and the international community that perception-based indexes are not accurate measures. It is obvious that perception and the experience of corruption are not the same things. Studies have shown that there is a wide gap between opinions and experiences from country to country.

Perception and reality are two different things. – Tom Cruise.

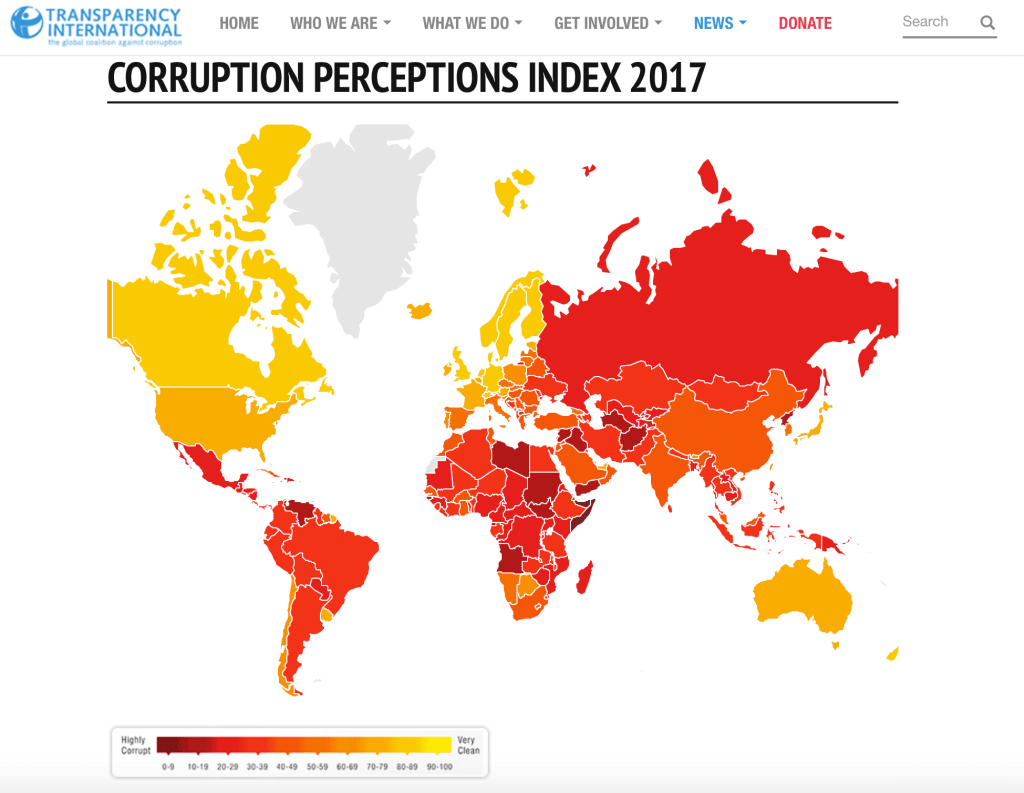

For the last 25 years, Transparency International (TI), a body comprising eminent persons from various countries, releases yearly reports on the corruption of about 180 sovereign nations. The findings or reports, termed, the ‘Corruption Perception Index’(CPI) ranks these countries and territories based on their perceived levels of, primarily, public sector corruption.

In its methodology of assessment, the Index uses a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 is the most corrupt, while 100 is the least corrupt. The information for the index is provided by ‘experts and business people’. For 2017, being the most current period, the Index found that more than two-thirds of countries scored below 50, with an average score of 43, meaning that more than half of the countries surveyed did not make the halfway line.

Consistent with past trends, the worst performing regions is Sub-Saharan Africa, with an average score of 32, and Nigeria scoring 27. That places Nigeria on the rank of 148, which is a drop of 12 places below where it was last year! Before we fret or celebrate over our new status, it is essential to highlight the methodology used in ranking countries.

Transparency International uses thirteen different data sources from twelve different institutions to construct the CPI: These are the African Development Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessment 2016; Bertelsmann Stiftung Sustainable Governance Indicators 2017; Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index 2017-2018; Economist Intelligence Unit Country Risk Service 2017; Freedom House Nations in Transit 2017; Global Insight Country Risk Ratings 2016; and the IMD World Competitiveness Center World Competitiveness Yearbook Executive Opinion Survey 2017. Also, the Political and Economic Risk Consultancy Asian Intelligence 2017; the PRS Group International Country Risk Guide 2017; World Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessment 2017; World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey 2017; World Justice Project Rule of Law Index Expert Survey 2017-2018; and Varieties of Democracy, 2017.

The main issue to address is not the complex statistical methodology it deploys, which it reassesses every two years, but the primary source of information it uses to arrive at its conclusion. For data sourcing, it uses ‘businessmen and credible institutions’ as a fount of information gathering. It is pertinent to indicate which type of business constitutes the sample size. Is it foreign or local? The ‘quality’ of the respondent matters in every research also. There will be a difference in the results of a survey if the persons that probably come for business with ‘hot’ money are prioritised over those that live in Nigeria and engage daily in different sectors of the economy. Transparency International further states that it collects parallel independent data from in-house researchers and two academic advisors, who are mainly expatriates. Although TI reports that it has no affiliation with the independent data sources, probably for ethical reasons, the technical methodology concerning where the independent sources obtain their data is not clear. Nowhere in the technical methodology is it stated that data is sourced from relevant institutions within a country that is being assessed.

Transparency International is very clear in its technical methodology that it does not capture citizens perceptions or experience of corruption! So where is the information or data generated from to support the ‘perception’ that reflects the reality of acts of public sector corruption in Nigeria?

By its admittance, most of the sources do not have global coverage. For a country or territory to qualify for assessment and ranking, there must be at least three CPI data sources from the earlier stated ones. So it is safe to assume that the African Development Bank, which is based in Africa and should know Africa, was the primary data collection point for Nigeria.

Therefore, the African Development Bank and at least two other institutions will collect data on matters regarding public sector corruption in Nigeria. They would also assess the ability of governments to contain corruption and enforce effective integrity mechanisms in the public sector. And then study the adequacy of the legal framework on financial disclosure and conflict of interest prevention. The data collecting organisations would equally ascertain whether there is legal protection for whistleblowers, journalists and investigators when they are reporting cases of bribery and corruption. Other areas of data collection include the confirmation of effective criminal prosecution for corrupt officials who divert public funds without excessive bureaucratic burden, which may increase opportunities for corruption. Quite important is that they are to look at the prevalence of officials using public office for private gain, without facing the consequences involved due to nepotistic appointments in the civil service or by narrow vested interests.

In the global standard for assessing complex criminal justice matters, such as money laundering, corruption or terrorism, researchers or assessors mainly look at the legal framework and see if its sufficient to combat such crimes. Next is the whether the institutions are capable of and have the technical capacity, funds, staff and other matters to implement the legal framework. Finally, there is the measurement or impact of the first two, which is usually the area where most countries have challenges.

In the areas enumerated above, could Nigerians laws be considered as robust enough and in compliance with international standards such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption? Are there institutions strengthened sufficiently to execute their tasks effectively? Are there data available and accessible by these agencies that would be contrary to data obtained from foreign experts? Transparency International is very clear in its technical methodology that it does not capture citizens perceptions or experience of corruption! So where is the information or data generated from to support the ‘perception’ that reflects the reality of acts of public sector corruption in Nigeria?

It also attributes the lack of journalistic freedom and engagement of the civil society to highly corrupt countries. The information is sourced from the data of the Committee to Protect Journalists, which indicates that every week, a journalist is killed in a country that is highly corrupt. It will be difficult to support that assertion in Nigeria because the state has sufficient press freedom, with no recorded casualty because of reportage of corrupt activities. In countries were journalists are killed, this is not usually as a result of speaking out against corruption but other factors, such as war or political assassinations. Also, there is not a single reported case of government highhandedness towards any civil society organisation that has spoken about corruption in Nigeria. All anti-corruption agencies actively engage with CSOs as partners in the war against public sector corruption.

The complexity of understanding how to interpret these indexes places the responsibility on anti-corruption agencies to explain index ratings to the media. That is probably why the Minister of Information was fidgeting on live television when trying to explain the CPI to the press because it didn’t make sense to him.

Furthermore, the ‘World Justice Project’ indicates that most countries that score low for civil liberties also tend to score high for corruption. Is there any evidence that Nigeria or any country in the sub-region is rated low on civil liberties or does not allow for civic participation? Most of the countries that scored high are old democracies with stronger institutions and based on that, will always have an edge and higher score over weaker democratic institutions. It is a constant that developed countries will typically rank higher than developing nations, due to stronger regulations.

Another problem with the ranking is that it is measured by a different methodology every two years and this would pose a challenge to making yearly comparisons. This significant subjectivity downgrades it as a tool for measuring the implications of new policies.

Part of its counter-productivity is that the ranking influences the actual perception of corruption because of the media attention they tend to receive. This raises the potential that the indexes influence the very same opinions on which they are based. Such circularity reinforces perceptions of corruption, creating a vicious cycle between perception and fact. Evidently, perceptions of corruption can be shaped by media and entrenched historical stereotypes. Therefore, the perception of corruption does not always reflect the reality or complexity of the actual level or experience of corruption.

There is growing concern among anti-corruption agencies and the international community that perception-based indexes are not accurate measures. It is obvious that perception and the experience of corruption are not the same things. Studies have shown that there is a wide gap between opinions and experiences from country to country. For example, in 2006 the CPI rated the United Kingdom as the 11th and Turkey as 60th in the index. However, using the Global Corruption Barometer, another form of measurement that is more of experience-based, reported that 98 percent of respondents, who were residents stated that they had not paid any bribe in the past 12 months. The incompatibility of corruption perception with the experience of corruption points to the shortcomings of the perception methodology used.

The complexity of understanding how to interpret these indexes places the responsibility on anti-corruption agencies to explain index ratings to the media. That is probably why the Minister of Information was fidgeting on live television when trying to explain the CPI to the press because it didn’t make sense to him. One can only imagine what would be going through the chairman of EFCCs mind that after going to Vienna in November 2017 and brandish a recovery of N739 billion, tons of asset recoveries, prosecution of hundreds of high profile cases and over ten countries drooling to copy the Nigerian model, the country only descends by 12 positions on the Index. Ridiculous I say!

Umar Yakubu is with the Centre for Fiscal Transparency and Integrity Watch. Twitter @umaryakubu